‘You’re all ink, so clean, just like a new newspaper.

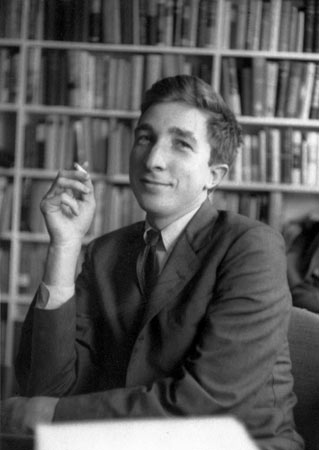

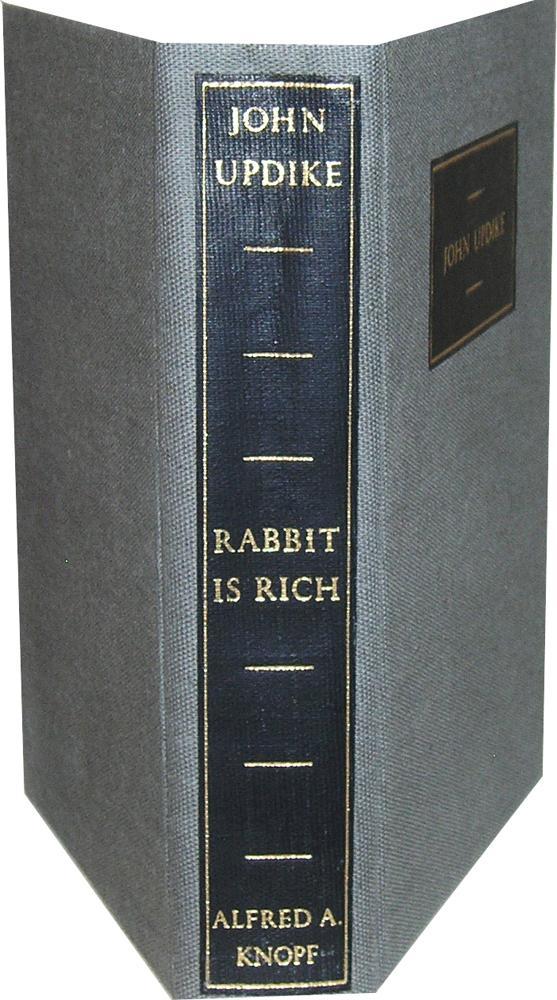

At one point, Rabbit comes home to his lover, Jill, and she pays him a compliment whose metafictional wit reveals Updike to be more than a complacent realist: “‘You smell of ink,’ she tells him. The novel reproduces newspaper articles as Rabbit sets them, mistakes and all. Leopold Bloom was an ad canvasser for a newspaper, and in Rabbit Redux, the title character is a typesetter, employed by the ironically named Verity Press. Modernism put this sacralization of reality to a particular kind of work: transfiguring the news, even as it brought it. You can dismiss this conception of the literary vocation as pious or old-fashioned, but, if you do, you are dismissing Joyce and much of literary modernism. In the preface to the collected Rabbit novels, “Rabbit Angstrom,” he talks about “the religious faith that a useful truth will be imprinted by a perfect artistic submission.” “The world is the host,” he has a character say in one of his short stories “it must be chewed.” Writing for Updike was chewing. “The Old Testament God repeatedly says he wants praise, and I translate that to mean that the world wants describing,” he once explained to an interviewer. He explained what he was up to many times. He wasn’t, as all those critics were essentially implying, masturbating. The most persistent and mindlessly recycled criticism of Updike’s work is that he was infatuated with his own style, that he over-described everything to no purpose-that, as several critics put it, he had “nothing to say.” But Updike wasn’t merely showing off with his style. In any case, Wood in his punitive Protestant iconoclasm would of course disparage Updike, since the novelist, as Louis Menand explains, belongs to the Joycean tradition of sacramental poetics from which Beckett was in flight: As James Wood wrote in The Broken Estate, “Updike, unlike Beckett or Bernhard, never appears to doubt that words can be made to signify, can be made to refer, to mean.” I admire Beckett and Bernhard, but I wonder what they would think of how their astringency has been made into a fashion statement by the Anglo-American literati. This facility has also been held against him. Updike, he said, was an American Shakespeare he could write about anybody and anything in any genre. A bias toward contrarianism-or perhaps metacontrarianism-makes me skeptical of the cool-kid consensus against the prodigious man of letters that has extended at least from David Foster Wallace’s overcompensatory try-hard male-feminist routine to Jessa Crispin’s exasperated middle-school “ugh.”Ī decade ago, a distant acquaintance urged me, over the noise of a crowded bar in Central Pennsylvania, to read Updike after I had unthinkingly repeated the cool-kid cliches. I will confess to wanting to like John Updike.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)